The teacher sat on her meditation cushion at the front of the large sunny hall. Behind her, placed prominently on the raised wood dais were statues—several feet tall—of the Buddha and Quan Yin.

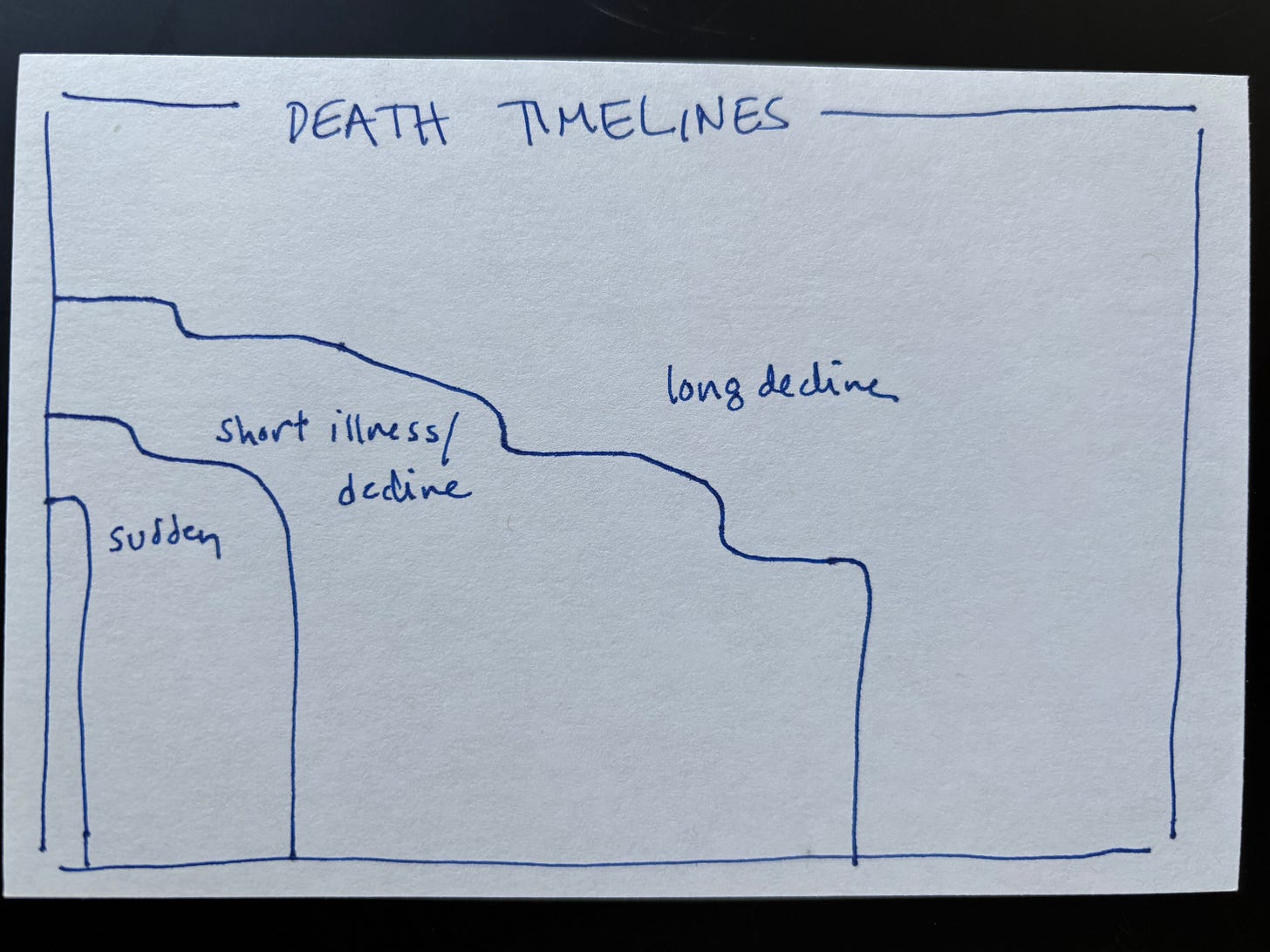

She directed our attention to the projection screen and a slide that looked something like this:

It was a graph depicting three different deaths.

a sudden death

death after a short illness

death after a long illness and/or slow physical decline

“Using a show of hands,” her voice was clear. “If you could choose one of these, how would you prefer to die?”

“Who would prefer to have a sudden death? One second you’re alive, the next you’re not.”

We were about 130 people, sitting on meditation cushions or on soft-seated red chairs or, for at least a dozen people, lying or sitting on thick navy-blue floor mats.

A large number of hands went up in the air. Number one was a popular option.

“What about death after a short illness?

My hand went up. A quick glance around the room. Other hands were in the air but definitely fewer than option number one.

“And lastly, who would prefer death after a long illness or a long and slow physical decline?”

I couldn’t scan the meditation hall quickly enough to see if any hands were raised at all.

We were a diverse group of people appearing to range from the early twenties to the late-eighties. We all self-selected for this particular week-long silent Vipassana meditation retreat. The focus? “Befriending mortality.”

The retreat at a local Insight Meditation center was based on the Buddha’s Maraṇasati practice, translated as “death awareness” or “death mindfulness.” The idea: living an awakened life through the mindfulness of death.

Each morning, the teaching team instructed us in one of the Buddha’s Maraṇasati practices. An example: one day our practice was—with every in-breath—to bring awareness to “this could be my last in-breath.” With every out-breath, “this could be my last out-breath.” Repeating.

An afternoon session focused on some element of death and dying—the three dying timelines or writing our obituary or, using the video screen, engaging in the practice of corpse contemplation with photos provided by “body farms” of human bodies in different stages of decomposition.

How would you prefer to die? the teacher asked.

My answer was born out of my experiences of dying and death.

My mother lived thirty days between her diagnosis and her death. That qualifies as a short illness. Those thirty days held a lot. My mother spoke of her surprise to discover that so many people cared about her. I’m still glad she experienced that. I felt her love for me—and that, too, remains a powerful and meaningful experience.

I don’t want to sugar coat that month. Those thirty days also held discomfort and physical pain. Fear and uncertainty for my mother—and for others of us, too.

I witnessed that—and, if I had a choice about my own death, I think I’d still prefer to have some time to say good-bye, to savor the people I love.

Perhaps every death we experience or come up close to is a teacher, shaping our experience with dying but also expanding our understanding of what dying and death could be.

One of my teachers was—and still is—Ann, a 58-year-old woman who, when the metastatic cancer treatments began to lose efficacy, asked me to officiate her memorial service, whenever the time came.

First learning: humans can hold seemingly contradictory POVs. At the same time Ann and I were meeting to discuss her memorial service, she was also consulting with her oncologist about a new treatment.

Planning her memorial service did not “jinx” the possibility of getting more time through a new treatment. She engaged both.

Second learning: In what turned out to be the last couple weeks of her life, Ann, feeling hemmed in by her mother and one of her brother’s too-close-attending to her physical needs, asked them to back off.

“I want to enjoy my death,” she told them.

Nearly ten years later, Ann’s words still ring in my body and blow open my mind.

“I want to enjoy my death.”

Okay then. So that’s a possibility, too?

At the meditation retreat, when the teacher shared that original slide of the different dying/death timelines, she mentioned one of her teachers.

Her mother lived with Alzheimer’s disease and experienced a long physical decline before her death. It was a quick, short jump for me between this anecdote and the teacher’s preference for the opposite.

Here’s something I think about a lot:

Death is universal.

Every death is particular.

Our experience of those unique events shape how we understand dying and death and think of our own.

But they don’t have to be static. Our understandings can grow, expand, change.

My mother’s death easily could have been different.

If she’d been in her rural home when she collapsed and not in a medical center for a treatment consult, odds are good she would have died quickly. All that transpired in those 30 days wouldn’t have happened.

My father, my sisters, me, her best friends, her sister—all of us would have had a different experience. Maybe we would be slightly different people. It wouldn’t be better or worse experience. Just a different path to walk.

I thought of that meditation retreat last week as I inhaled Geraldine Brooks’ new memoir Memorial Days about her husband Tony Horwitz’s sudden death and her life after. A cardiac event at sixty years old. They lived on Martha’s Vineyard but he was on a book tour in Washington DC. Remarkably he collapsed in ambulance-proximity to the hospital where he was born. It became the hospital that declared his death.

The memoir moves between the immediate aftermath of Tony’s 2019 death and several years later when she returns to a small island in her native Australia to give herself time and solitude to remember and grieve—something that wasn’t possible before.

She writes:

I put the journals aside and go walking, marveling at how little we can know of our future, fretting that the Tony of 1989 had no sense how bright and successful his career was quickly about to become.

As I kick the sand, the corollary occurs to me.

I’m thankful that the Tony of 2019 had no sense that his future was about to vanish abruptly, on a street corner, with a plummet into the dark. We know both things are possible—the glittering prize, the sudden fatality. We dare to imagine the former. Most of us deny the latter. Deny it, even when it confronts us.”

On a chilly evening three months before he died, Tony walked into the kitchen looking stricken. Lincoln, one of his oldest childhood friends, an art professor in DC, had died of a sudden heart attack. “He was only sixty and he just dropped dead.” Tony raked a hand through his hair as I hugged him. What a crazy thing, I thought, to die so young and so suddenly. How awful for his wife, his kids. I did not see how this news might relate to us. I did not think, Tony could be Lincoln; I could be that wife.

How could I have been so blind?

My teacher prefers a sudden death. I* prefer one after a short illness.

[* the “I” writing this—in May 2025, in my late 50s and presenting as physically healthy. But if my circumstances change, maybe my preference will too. Perhaps I’d be okay with a long decline in my 50s, but not in my 80s. “I learn by going where I have to go.”]

Our preferences are likely irrelevant. Our deaths will likely be what they will be.

But Ann, my teacher, reminds me that I can hold opposite ideas simultaneously. I can prefer death after a short illness and prepare for something different.

Geraldine Brooks, in her memoir’s Afterward, offers some counsel, born out of her lived experience. Some knowing she didn’t have before Tony died.

“I have a proposal that is an individual practice, something anyone can do—a simple habit for people in a long partnership. Jot down all the tasks you don’t bother to mention that keep the household afloat, the set of torches that only you have learned to juggle. All the little things your partner didn’t expect to need to know, until the day they never expected to happen.”

My friendly amendment to her words: this wisdom is for everyone, regardless of partnership. Because any sudden death means some beloved—niece, nephew, best friend, cousin, sibling, parent—is left to figure out everything (passwords, billing, pets, body disposition, rituals) at one of the worst moments of their life.

I’m the handy one in my household. I know how to check the magnetic filter on the hot water system and what valve to open if the expansion tank psi drops too low. In my google drive there’s a document called HOME where I mean to download all the house-stuff that lives in my brain so someone—besides me—knows.

I’ve added info about the wireless router and passwords. The contact info for the Bill, the heating system magician. But there’s a lot more needed.

It’s not fun work. It requires rooting around in old file folders. It takes longer than I think it will. My resistance to the task expands like a balloon in my chest and I easily float away.

Except now I have Geraldine Brooks’ story in my head.

The legal documents, the canceled health insurance, the unpaid taxes. Her experience expands my understanding of a sudden death and its aftermath. What do I want to leave for the ones who love me?

If I spend a week sitting in a meditation hall, repeating “this could be my last breath,” surely I can finish that google doc? Tie that balloon of resistance to a rock and stick with writing down the details that will make life easier for my people when I die.

“Death mindfulness” practice brings a person into a more immediate relationship to their mortality. I think I’ve found one particular practice for Summer 2025. Want to join me?

As always, I look forward to the conversation continuing in the comments. If you wish, I hope you’ll share your thoughts, questions and responses.

Thanks for reading —

Until next week,

Rachel

Thanks, Rachel. I learned from my mother's partner's death that we cannot know what death we will want in the end. Frank was a robust, fully functioning 90-year-old when he learned that he was full of cancer and had only a month left to live. That's my idea of a perfect death. But not his.

When I visited Frank in the hospital he was despondent. "You know you are going to die sometime, but you never think it's going to happen to you," he sobbed. Even after 90 years of good health, Frank felt cheated.

Since Richard's death, I've been saying that I think couples should switch roles every now and then, just for a couple weeks, to get some sense of what their mate does. I've also been meaning to start my own file of all those things my kids would need to know when I die. Like you said, it's a boring, tedious task! Inspired by you, I've now set up a file in NOTES, titled it WHEN. I guess the next thing I should do is let the "kids" know how to get into my computer and where this file will be. Gulp! I wish there was a class on this.