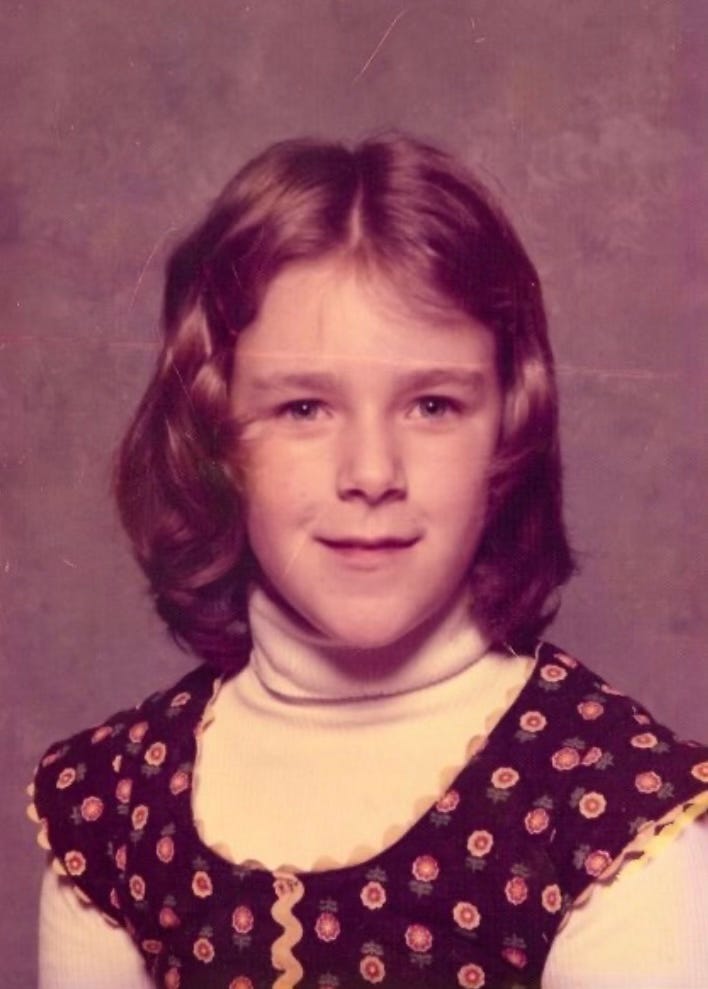

This is eight-year-old me.

This kid has a Jewish mother, a Christian father and a helluva ritual life.

On Friday nights she attends services to mark the beginning of the Sabbath—the day of rest and worship—at the local Reform (Jewish) synagogue. The sanctuary is a compact rectangular room with dark wood walls and short pews with soft red velvet cushions. She loves eating the soft, white puffy bread shared after the service.

The following morning, on Saturday, little Rachel returns to synagogue for Sabbath School, weekly age-grouped classes, where she learns Hebrew letters and stories from the Hebrew Scriptures. (Moses parting the Red Sea, Esther the Queen, Noah’s Ark are faves). Snacks are involved.

It’s in one of these linoleum-floored classrooms where she first attempts to answer the question “What are you?” With her index finger, she draws a line down the middle of her body, from head to knees. Pointing to one half, she explains “This is my Jewish half,” and, then, pointing to the other, “And this is my Unitarian half.”

It’s in one of these linoleum-floored classrooms where she first attempts to answer the question “What are you?” With her index finger, she draws a line down the middle of her body, from head to knees. Pointing to one half, she explains “This is my Jewish half,” and, then, pointing to the other, “And this is my Unitarian half.”

Because Sunday morning finds her at the local Unitarian Universalist congregation’s worship service. This sanctuary is modern and octagonal, with a ceiling stretching forty feet high. The pews are long and the cushions are scratchy. No velvet here. But there are age-grouped religious education classes in linoleum-floored rooms. Here she learns about Pandora, Persephone and Jesus the Rabbi. Sometimes the class takes field trips to other churches and synagogues; when they visit Temple Beth Jacob, she encourages her friends to stroke the red velvet cushions.

Twenty years later and 3000 miles to the west, I was ordained a Unitarian Universalist minister. “The Reverend” became my prefix. I was 29 years old. My professional ministry varied. As a hospital chaplain I provided spiritual care to adult patients and staff with a range of spiritual and religious identities, including many who would claim “none of the above.” I was the solo minister of a small multi-generational Unitarian Universalist congregation where the chairs (no pews) were filled by people with a wide range of theological beliefs.

When my wife and I welcomed twin sons in the early aughts, my professional life shifted to supporting colleagues and ministers-in-training. Over the past dozen years, my ministry focused on end-of-life rituals and accompaniment with individuals who didn’t identify with a particular religious tradition. During the pandemic, I coached people who wanted to create rituals to mark deaths and other losses.

Over the twenty-eight years I served as a UU minister, I continued the modified Jewish home rituals my mother modeled for me and my younger sisters: honey cakes to mark Rosh Hashanah, fasting on Yom Kippur, kindling Hanukkah menorahs, Passover seders with other Half & Half families and throughout the year, marking death anniversaries by lighting jahrrzeit candles, burning through the night.

“Why do you want to be a minister?”

I had a lot of answers. All were true.

I want to be a spiritual companion to children and adults, seeking that which matters most. I want to help repair the world. I want to create a space where people bring their whole selves, where we sing together and give thanks together and make meaning of being alive. I want to be with people at births and deaths. I want to lead. I want to be like the first woman minister I saw in the pulpit.

I had a lot of answers. All were true.

But the list was incomplete.

“[Religion is] our human response to the dual reality of being alive and having to die."

One of the gifts of living—of aging—is being able to look back at the circuitous path that led us from There to Here. Like standing on a ridgeline in the East Bay hills looking west towards San Francisco Bay, and gaining a new perspective of the trail I just hiked up. I remember the sweaty section and then the relief of trees. Now I see how the trail hugs the exposed hillside, before ducking into a shady stand of Live Oaks.

Looking back, I see I needed a new way to get closer to death—and religious leadership offered a path.

The story below the story below the story.

When she was 29 years old and parenting a fifteen month old baby (me), my mother was diagnosed with a potentially fatal cancer at a time when “long-term survivors” didn’t exist—neither the phrase nor the people it would later describe.

It was the late 1960s. If you survived a cancer diagnosis and treatment there were no emotional support groups. There were no psychological resources. What there was, was secrecy, isolation, job insecurity and—always—fear of recurrence.

Remarkably, joyously, my mom would became one—a long-term survivor. But the early-in-life diagnosis and treatment, along with an abiding uncertainty around her mortality, resulted in her lifelong deep anxiety about dying.

For much of my early life, that anxiety remained a quiet, reserved presence in our home but there were times it was big, tearful and terrified.

I grew up with my mother’s fear of dying and a preternatural, keen awareness of loss.

And then I followed a professional path that let me approach, explore and make meaning of death and dying in different ways with different people. As a Unitarian Universalist minister, I helped mourners find ways to integrate death into their living.

What I didn’t see until recently is that I’ve been trying to do that most of my life.

I officially retired from the professional ministry last year. That path ended, and now I’m bushwhacking a new trail. The destination is unknown. I know it’s cliche—and cringy—but maybe it really is all about the journey?

I’m still seeking to understand that dual reality of being alive and having to die.

I’m still curious about how ritual can both contain and transform loss and grief.

I’m still integrating death into my living.

Marking What Matters is my report from the trail. I’m grateful to share it with you.

Mama’s gone and done it again❤️🔥

I can't wait to read more. Keep writing.